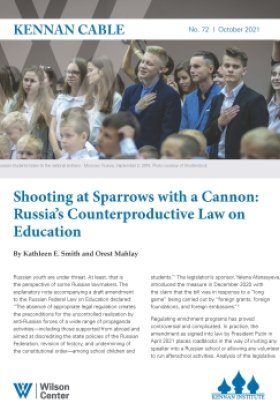

Kennan Cable No. 72: Shooting at Sparrows with a Cannon: Russia’s Counterproductive Law on Education

Russian youth are under threat. At least, that is the perspective of some Russian lawmakers. The explanatory note accompanying a draft amendment to the Russian Federal Law on Education declared: “The absence of appropriate legal regulation creates the preconditions for the uncontrolled realization by anti-Russian forces of a wide range of propaganda activities—including those supported from abroad and aimed at discrediting the state policies of the Russian Federation, revision of history, and undermining of the constitutional order—among school children and students.”[1] The legislation’s sponsor, Yelena Afanasyeva, introduced the measure in December 2020 with the claim that the bill was in response to a “long game” being carried out by “foreign grants, foreign foundations, and foreign embassies.”[2]

Regulating enrichment programs has proved controversial and complicated. In practice, the amendment as signed into law by President Putin in April 2021 places roadblocks in the way of inviting any speaker into a Russian school or allowing any volunteer to run afterschool activities. Analysis of the legislative history of the law on educational activities [prosvetitel’skaia deiatel’nost’] demonstrates both the priorities of the Putin regime and the flaws of its rubber stamp legislature.

Bringing Order to the Sphere of Education

How did a proposal to “protect” young people end up threatening to deprive them of access to afterschool drama clubs and talks by astronauts and war veterans? The new law attempts to regulate educational activities [prosvetitel’skaia deiatel’nost’]. The key Russian word in the law, prosveshchenie, can be translated as education or enlightenment and carries a positive connotation: It implies the charitable and noble aim of spreading knowledge. Lawmakers needed a concrete definition for educational activities, but only came up with a very broad characterization: “activities carried out outside the bounds of official educational programs that are aimed at the dissemination of knowledge, abilities, skills, development of values, experience and competence for the purpose of intellectual, spiritual-moral, creative, physical and/or professional development of a person, satisfaction of his educational needs and interests.”[3] In short, the law would cover all kinds of sharing of knowledge.

The law bans using enrichment activities for “inciting social, racial, national or religious hatred;” communicating “inaccurate information about the historical, national, religious and cultural traditions of peoples;” or “inciting activities that contradict the Constitution of the Russian Federation.” A second aspect of the law empowers the federal government to review and potentially refuse permission for projects that involve cooperation with foreign actors.[4]

With its sweeping definition of educational activities, the law seems likely to affect everyone from professionals who share their knowledge with the public to enthusiasts who run extracurricular clubs for children. The bill’s sponsors recognized that their law would affect tens of thousands of educators, not just school teachers, but also university professors and experts from the Academy of Sciences. The sponsors argued that the high demand for educational content justified the need to establish regulatory norms.[5] The scenarios raised by the law’s supporters in the first reading in the Duma, however, had little to do with typical enrichment activities.

The sponsors invoked geopolitical threats—including from ISIS and unspecified Soros-funded programs. Deputy Vyacheslav Nikonov warned against all sorts of Western-financed initiatives, blaming them for having turned a whole generation of Ukrainians against Russia. Regarding academic exchanges, he falsely claimed that: “every American scientist who contacts any Chinese scientist or Russian scientist on a scientific matter writes reports on each of his contacts and is under the full tutelage of the FBI, these contacts are all simply tracked.” Afanasyeva highlighted the need to be worried about children’s safety, noting that: “Today there were [discussed] many draft laws concerning foreign agents. These are grown-up people who made the decision that they wanted to do such work... But [here] we are talking about children who fall under the influence of adults.”[6]

The narrow, securitized perspective on educational activity taken by the bill’s sponsors (all of whom serve on either the Federation Council’s Commission on Defending State Sovereignty and Combating Foreign Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs or the Duma Commission for Investigating Facts of Interference by Foreign Governments in Russia’s Internal Affairs) aroused some discontent within the legislature. The most active parliamentary opponent of the amendment, Communist Party of Russia Deputy Oleg Smolin (a former president of the “Knowledge” society and an educational specialist) was upset that the bill did nothing to promote educational activity. As he saw it, the spirit of the law contradicted the Russian tradition of viewing enlightenment activities as a public good. ISIS recruitment programs, he argued, had nothing to do with education; hence, a desire to quash terrorist recruitment should not motivate imposing onerous bureaucratic controls on a whole sector. He suggested the law should exclude “educational activities” and only regulate agreements between educational institutions and foreign partners.[7]

Instead, the sponsors of the amendment used its pedigree as a product of their patriotic commissions to cut off criticism. At the bill’s final reading, Nikonov challenged his fellow deputies: “And if someone is going to speak against [the bill] now, I will have one question: for whom are you working?”[8] Similarly, Andrei Klimov, President of the Federation Council’s Commission on Defending State Sovereignty and Combating Foreign Interference in Russia’s Internal Affairs, told journalists that opposition to the bill originated in Washington. “We know perfectly well when and from where signals were sent out and along which lines…This absolutely is not some school teacher or lecturer from some university or another in the Urals.” Klimov even claimed that a protest by the board of the Russian Academy of Science had been incited by foreign forces.[9]

Despite such discourse aimed at discrediting any opposition, the law faced substantial and multifaceted pushback especially as regards the attempt to regulate ordinary educational activities. Though the law passed the Duma with 308 votes in favor, 95 against, and 1 abstention, deputies from the Communist Party of Russia and the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia raised substantial concerns about bureaucratization, curtailment of spaces for free discussion, and a general squelching of valuable programs. Experts and citizens expanded on these critiques.

Public Reaction and Criticism from Academic Circles

Academic communities from the cultural and scientific spheres led the pushback against the draft law on educational activities, with legal commentators disputing the constitutionality of the bill. Open letters written by artists and curators, scientists and those who facilitate educational activities, especially in the sciences, garnered the most coverage. Astrophysicist Sergei Popov’s change.org petition demanding that these changes to the law be rescinded collected over 248,000 signatures, as well as comments outlining the law’s different flaws. Major criticisms included the isolationist nature of the law, the possible increase in censorship, the law’s broad and vague scope, as well as an overarching concern regarding constitutionality. The open letters also noted the law’s potential to deprive Russian society of a variety of academic resources.

One of the major criticisms against this law focuses on the question of constitutionality. An open letter from artists and curators outlined the constitutional rights that would be violated if the government passed the law: the “right to education,” “right to seek, receive, transmit, produce and disseminate information,” and the “freedom of literary, artistic, scientific, technical and other types of art and teaching,”[10] all of which are guaranteed in Article 29 of the Russian Constitution.[11] However, as comments to the change.org petition reiterated, many fear that these broad powers outlined by the law given to the central government for oversight and certification of formal and informal exchange of knowledge will violate these constitutional guarantees and open the door to selective censorship.[12]

Those who support regulation presented the amendment as providing a legal framework where one was absent. Its critics contended that the proposed changes as written were largely duplicative and hence unnecessary. Existing laws defining undesirable organizations already block groups deemed as dangerous from conducting activities in Russia, and Article 282 of the Criminal Code outlaws inflammatory speech. Legal scholar Ekaterina Mishina points out that, “It would seem that the country’s mighty past is effectively protected by both the Criminal Code’s Article 354.1 (“Rehabilitation of Nazism”) and Article 67.1 of the Constitution, while Russia’s constitutional order enjoys even greater protection.”

Besides duplicating existing codes, the new legislation also puts pressure on educational activities by mandating increased oversight from state officials. Mishina concludes that, “the amendments to the Federal Law on Education are not in fact aimed at defense, rather at the stigmatization of independent educational projects and the placement of non-official educational activities under the strict control of the state in order to eliminate freethinking and dissent. Their goal is to present independent educational activities as inherently malicious.”[13]

Opponents to the law also raised the issue of bureaucratization, anticipating that the Ministry of Education would be swamped with requests. Given the broad nature of the law, it wouldn’t just be schools wanting to do direct exchanges or universities inviting visiting scholars that needed permission, but online lectures, museum exhibitions and so forth—especially if they involved foreign contacts. Curator Lizaveta Matveeva, who helped write the collective letter from figures in the art world against the amendment, warned of the likely selective implementation of the law since: “Of course, no one will analyze all educational projects, since [officials] will drown in the bureaucracy. But at any moment, when someone does something they dislike, it will be possible to use this law and hold [those facilitating these projects] accountable.”[14]

Opponents have also noted the danger of Russian educational institutions becoming more isolated from peers and experts beyond Russia’s borders, since the new law requires the approval of all educational exchanges with both foreign institutions and individuals. As the open letter from artists and curators states: “the lack of an opportunity to build stable ties with the international professional community on a permanent basis will inevitably lead to a lag in the development of culture, science and education in our country.”[15] Another open letter, written by the creators and leaders of 17 educational organizations, specified that the barriers for the advancement of educational activities would not only hurt those who need this information, but “will affect the trajectory of development of the entire Russian society.”[16] Across these different academic communities, public statements articulate concerns surrounding isolationism and a possible decline in the quality of educational activities being offered.

Although academic communities have voiced their opposition to the law, the response from the public has been minimal. In April of 2021, the Levada Center released data from an opinion poll they conducted amongst the Russian public; 71 percent of Russians never heard anything about the law, while only 6 percent were well-informed about the passing of this law.[17] While users of Telegram and other social media platforms were more likely to be aware of the passage of this law, average Russian citizens were ignorant of or had very limited information about this recently passed law, even after months of pushback and criticism by various academic and professional circles. The data suggests that the public is either indifferent to these developments or is not accessing less-regulated internet sources that highlighted the controversy around the bill. (State-controlled media covered the law as simply bringing order to the educational sphere.)[18]

Given United Russia’s supermajority in parliament, the bill passed by a large majority. The final version did not reflect any of the criticism offered inside the legislature or from outside. The new law relegated all problems of clarity, scope, and constitutionality to the agency responsible for implementing the law, the Ministry of Education.

When the Rubber Hits the Road

As of August 20, 2021, more than two months after the law was supposed to come into force, the Ministry of Education had produced only a draft decree addressing educational activities with rules for projects involving foreign partners yet to come. As with the law, the decree prompted scathing reviews. An event held by the Public Chamber (a consultative organ that includes representatives of social organizations and whose mission includes oversight of draft legislation) with Deputy Minister of Education Andrei Korneev exposed a myriad of technical and fundamental problems.

The draft decree laid out a working definition of “educational activities” for the purposes of the new law—namely, seminars, master classes, roundtables, and discussions. The decree also included distribution of materials in printed form or through the internet, how-to demonstrations whether in person or video or audio guides, and the creation of educational portals on the internet. In terms of content, enrichment included everything from disseminating knowledge of civil rights and popularizing science to advising on career paths and publicizing the “spiritual-moral values of the peoples of the Russian Federation.” Now all such work would be carried out under contracts between the person providing the education and the subjects of those services.[19]

Persons who wished to offer enrichment content had to meet certain requirements. They could not be minors and had to prove that they had already carried out similar activities for at least two years. They would also be subject to the same rules that governed eligibility to teach in Russian schools—including no record of serious crimes or sex offenses, and the absence of certain infectious diseases. Organizations providing educational programming, including businesses, would be required to publish certain information about themselves on their websites; they would have to be up-to-date on all taxes, and could not have the status of “foreign agents.” Their employees or volunteers would also have to meet the standards for teachers mentioned above.

Both the specifics and the broader direction of the law generated pushback. How could one definitively prove two years of experience in educational activities? Representatives of small business and the self-employed pointed to the prevalence of young people in offering tutoring and music lessons and asked why they would be disqualified based on age. Others wondered what tax arrears had to do with competency and what to do about small organizations that did not have internet presences.[20]

The greatest confusion surrounded the potential scope of activities to be regulated. At the Public Chamber meeting, Deputy Minister of Education Andrei Korneev confirmed orally that the proposed implementation document did not extend supervision to the internet or other forms of media, but rather forbade random people “from the street” from being part of afterschool programs. Similarly, it seemed that the ban on inciting national and ethnic hatreds and so forth would be enforced solely against licensed educational programs.[21] Korneev further admitted that there had already been discussions with the Ministry of Culture about excluding cultural institutions from the law. The Russian Orthodox Church, according to Kommersant, also had requested an exemption for Sunday Schools.[22]

Korneev’s assertion that the law would be imposed in schools and licensed institutions and not against the internet, publishing in general, or independent business did not console those who would have to deal with the rules in practice. At the Public Chamber’s forum, Avdotia Smirnova, founder of a charity that educates parents and teachers about autism, protested that her organization would close down if it had to clear every speaker for every school visit. It would also be too laborious to sign contracts with every school where children with autism were being mainstreamed. Similarly, Sergei Bogatyrev, representing the national committee of museums, contended that his institution, the Museum of the Russian Icon, would simply cease hosting conferences. Moreover, several members of the Public Chamber suggested that as with any law requiring licensing this decree would promote corruption.

A consensus emerged at the Public Chamber’s meeting with the deputy minister of education that the regulations as proposed would discourage principals and departments from allowing any enrichment activities due to the paperwork involved and fear of being held accountable in case of some errors or overly zealous enforcement. Although the draft decree did not specify any administrative or criminal penalties, it would be intimidating if enacted. While even the most hawkish participant in the discussion did not want to block visits by veterans or prevent talks by police officers on traffic safety, these activities would also likely fall by the wayside. The perceived benefits lawmakers had in mind of preventing those rare cases of dangerous or inappropriate lessons did not merit the very real burdens they had created for Russian schools.

An Impossible Law

Unlike more targeted laws against organizations that are seen as representing foreign interests, the amendment to the Law on Education cast a wide net over every enrichment activity at every school. It created a daunting task for regulators and a terrible burden for practitioners. In the words of Mikhail Gelfland, Doctor of Biology: “The law is stupid and illiterate. Its consistent application is impossible, and the selective one places the threat of punishment over anyone engaged in educational activities....”[23] The bill’s authors took a cavalier attitude toward the sloppiness and impracticality of their creation. One sponsor told journalists, “According to our law, the government will deal with these nuances. Let's hope that before the government approves this resolution, it will study the proposals, criticism, and take into account people's opinions as much as possible.”[24]

The sponsors of the new law succeeded in taking a symbolic stand against foreign influences, but put the onus on the executive to resolve a host of issues concerning clarity and constitutionality. However, their performative patriotism came at the cost of discouraging a wide range of non-political enrichment activities for Russian students. The case of the law on educational activities demonstrates that a legislature dominated by an obedient majority can produce efficiency, but not guarantee quality. The genesis of the amendment shows the regime’s current obsession with fighting foreign influence. The results show the price of its incompetence as a “patriotic” law threatens to choke off educational opportunities across the board.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the authors.

[1] “Poiasnitel’naia zapiska k proektu federal’nogo zakona ‘O vnesenii izmenenii v Federal’nyi zakon “Ob obrazovanii v Rossiiskoi Federatsii”’.” Available at: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1057895-7#bh_note.

[2] Elena Afanasyeva in “Stenogrammy obsuzhdenii” (Session 333, December 23, 2020). Available at: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1057895-7.

[3]“O vnesenii izmenenii v Federal’nyi zakon ‘Ob obrazovanii v Rossiiskoi Federatsii’.” Available at https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1057895-7.

[4] “Poiasnitel’naia zapiska.”

[5] Liubov’ Dukhanina in “Stenogrammy obsuzhdenii” (Session 333, December 23, 2020). Available at: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1057895-7.

[6] Elena Afanasyeva and Viacheslav Nikonov in ibid.

[7] Oleg Smolin in “Stenogrammy obsuzhdenii” (Session 333, December 23, 2020). Available at: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1057895-7.

[8] Viacheslav Nikonov in “Stenogrammy obsuzhdenii” (Session 345, March 16, 2021). Available at: https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/bill/1057895-7.

[9] Klimov cited in Natal’ia Kostarnova and Andrei Chernykh, “Prosvetitelei prosvetiat na sviaz’ s Vashingtonom,” Kommmersant, Jan. 14, 2021. Available at: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4641656.

[10] “Otkrytoe pis’mo ob otklonenii zakonoproekt nomer 1057895.” Available at: http://aroundart.org/2021/02/04/otkry-toe-pis-mo-soobshhestva-s-trebovaniem-otklonit-zakonoproekt-1057895-7/.

[11] https://rm.coe.int/constitution-of-the-russian-federation-en/1680a1a237.

[12] “Protiv popravok o prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti.” Available at: http://chng.it/nkFFRqKvMp.

[13] Ekaterina Mishina, “Why does the Russian government keep making enemies out of educators?” Institute of Modern Russia, March 3, 2021. Available at: https://imrussia.org/en/analysis/3243-why-does-the-russian-government-keep-making-enemies-out-of-educators. On selective prosecution and anti-extremism laws, see William E. Pomeranz and Kathleen E. Smith, “A Traditional State and a Modern Problem: Russia Rewrites its Internet Extremism Laws,” Kennan Cable, no. 39 (December, 2018).

[14]Cited by Sophia Kishkovsy, “Russian culture figures fear new law change will require government approval for museum tours, exhibitions and lectures,” March 15, 2021; available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/russian-education-law.

[15] “Protiv popravok o prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti.”

[16]“Deklaratsiia uchenykh i populiarizatorov nauki,” available at https://trv-science.ru/2021/01/declaration/.

[17] “Zakon o prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti.” Available at: https://www.levada.ru/2021/04/12/zakon-o-prosvetitelskoj-deyatelnosti/

[18]See for instance, Tat’iana Zamakhina, “V Rossii uzakonili prosvetitel’skuiu deiatel’nosti,” Rossiiskaia gazeta, March 16, 2021; available at: https://rg.ru/2021/03/16/gosduma-priniala-zakon-o-prosvetitelskoj-deiatelnosti.html.

[19] The draft decree “Ob utverzhdenii Polozheniia ob osushchestvlenii prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti” is available at: https://regulation.gov.ru/projects?fbclid=IwAR1JrW1axt7WBnC4JIwIhsRZqcXS5PHLDu5rcVVQgxpPs599TJwyRoJ6ki0#npa=115396

[20] A video recording of the Public Chamber’s discussion forum on the proposed regulations--“Obsuzhdenie proekta postanovleniia Pravitel’stva o prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti”--is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOP-VT0Q9mk.

[21]Ivan Akimov, “‘Blogeram novye soglasheniia zakliuchat’ ne nuzhno,’” Gazeta.ru (April 21, 2021. Available at: https://www.gazeta.ru/tech/2021/04/29_a_13577114.shtml.

[22]Anna Vasil’eva, “Ot prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti osvobodiat muzei i biblioteki,” Kommersant, April 29, 2021. Available at: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/4799365#id2048945.

[23]“‘Glupo i bezgramotno’: uchenye vystupili protiv Zakona o prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti,” Novye izvestiia, January 11, 2021. Available at: https://newizv.ru/news/society/11-01-2021/glupo-i-bezgramotno-uchenye-vystupili-protiv-zakona-o-prosvetitelskoy-deyatelnosti.

[24]Andrei Al’shevskikh cited in Iana Shturma, “O blogerakh ne podumali: kak budet rabotat’ zakon o prosvetitel’skoi deiatel’nosti,” Gazeta.ru, April 26, 2021. Available at: https://www.gazeta.ru/social/2021/04/26/13572848.shtml?updated.

Authors

Professor of Teaching, School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

How Education Can Empower Young Women in MENA