A blog of the Kennan Institute

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainians have displayed extraordinary unity in the face of existential threat, debunking the Russian propaganda narrative of a long-existing schism in society. Nearly three years into the full-scale war, Ukraine’s unity faces a litmus test: Are the divisions real, or are they part of an external narrative aimed at undermining resolve from within?

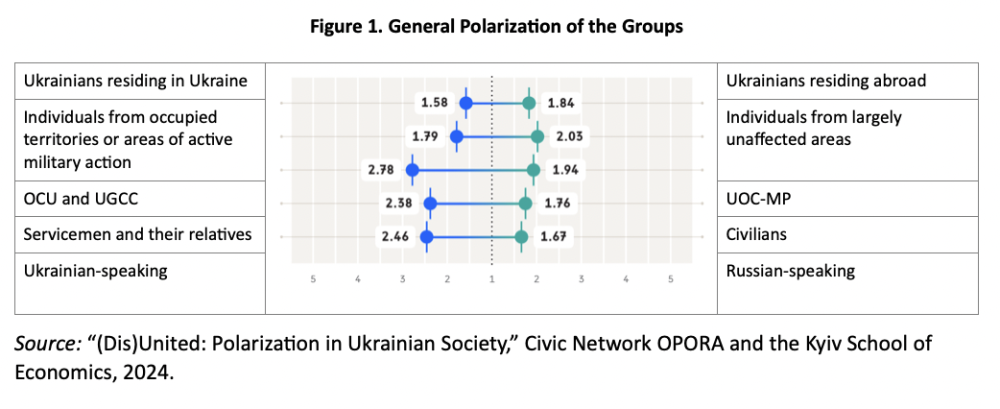

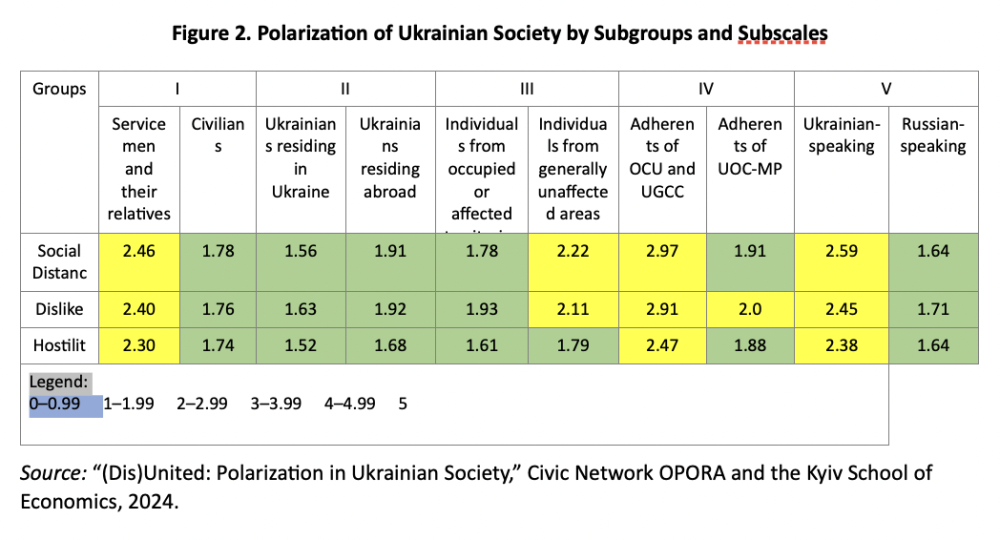

In September 2024, a study titled “(Dis)United: Polarization in Ukrainian Society” by Civic Network OPORA and the Kyiv School of Economics offered a closer look at alleged polarization within Ukraine. The research surveyed 2,055 individuals across five distinct groups, examining potential divides between those serving in the armed forces and their relatives versus civilians; between those who left Ukraine and those who stayed; between individuals from occupied territories or areas of active military actions versus those in unaffected areas; between adherents of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU) and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC), on one side, and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP) on the other; and between Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking populations.

The average polarization index for each group, calculated from twenty-eight items, ranges from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating greater polarization. In all cases, averages fall below 3, indicating that while respondents may hold some dislike, they generally do not feel strong hostility toward opposing groups.

Most groups, particularly Ukrainians living abroad and those residing within the country, express minimal emotional distance toward one another.

Religion, however, did emerge as a fault line, with greater social distance and distrust evident between members of the OCU and the UGCC, on the one hand, and the UOC-MP on the other. This can be explained by the role some UOC-MP clergy have played in promoting Kremlin propaganda and supporting the invasion. But even within these religious divides, respondents were not inclined to openly express hostility, underscoring an unwillingness to go beyond mere distrust.

The social distance between individuals who have lived in temporarily occupied territories (TOT) or combat zones and those who have not is relatively small. However, they perceive that the other group tends to judge them negatively, which may complicate their interactions despite the lack of real antagonism.

Ukrainian-speaking and Russian-speaking populations are not hostile to each other either. Nonetheless, Ukrainian speakers are more likely to perceive Russian speakers as untrustworthy, while Russian speakers tend to see Ukrainian speakers as indifferent. Interestingly, both groups agree that they enjoy seeing representatives from the other group being put in their place.

This divide primarily stems from the Kremlin's ongoing exploitation of the protection of Russian-speaking populations as a pretext for its aggression. The Kremlin incorrectly associates Russian-speaking individuals with the notion of the "Russian world," which serves to justify its military actions and political maneuvers in Ukraine. This assumption not only misrepresents the diverse identities within Ukraine but also seeks to legitimize a narrative that frames Russia as a protector rather than an aggressor.

People with military experience and their families tend to feel somewhat more distant from civilians than vice versa. This can be explained by a growing fatigue among servicemen while Ukraine is looking for ways to overcome mobilization issues and ensure rotation.

Interviewees were also invited to assess their attitude toward imaginary people with different combinations of characteristics reflecting the five points of division. Respondents had a notably negative view of imaginary persons who exhibited two specific traits: continuing consumption of Russian information products while dodging military service. Traits that boosted positive perceptions included serving in the military and actively rejecting Russian media content. In a landscape where national identity and loyalty are paramount, these characteristics resonate strongly with audiences.

Yet the most revealing finding was not about actual divisions but about perceived ones. Although the data showed minimal polarization, many Ukrainians believe that society is deeply divided, an assumption amplified through social media, anonymous channels, and in particular political rhetoric. This perception gap suggests that Ukrainians are highly susceptible to narratives that emphasize division, even when these divides aren’t substantiated by the data.

Russian disinformation campaigns effectively employ a divide-and-rule strategy to manipulate public opinion. Anonymous Telegram channels—many influenced by Russian disinformation tactics—reinforce the notion that Ukrainians are fractured along ethnic, linguistic, and regional lines.

Ukrainians, meanwhile, have been exposed to this narrative long enough that many now see divisions as inevitable. Each time they discuss these alleged divisions, they unwittingly reinforce this Russian myth, which should not transform into a self-fulfilling prophecy. The greatest threat to Ukraine’s unity, therefore, is not inherent social polarization but the idea that such polarization is unavoidable.

The survey data indicate that while divisions do exist in Ukrainian society, they are neither deep nor unbridgeable. Ukrainian society remains remarkably consolidated, with no alarming animosity between groups. Differences are largely contextual and do not constitute irreconcilable fault lines.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Authors

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in Focus Ukraine

Browse Focus Ukraine

Talking to the Dead to Heal the Living

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections