On December 19, 2023, the United States announced for the first time the outer limits of its extended continental shelf (ECS), the portion of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the coast. The United States is a major maritime nation with the largest exclusive economic zone in the world, and this historic step helps protect its sovereign rights to vast additional subsea areas. It is also an important milestone reflecting US engagement with the law of the sea as reflected in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and as an aspect of advancing major US interests in the Arctic and other regions.

Other articles in this compilation provide background related to the announcement. Although it will take time to consider the details of the extensive Executive Summary and gauge the international reaction to the U.S. determination, here are some key initial takeaways.

1. The announcement was necessary to protect long-term US national interests

It has long been clear that the United States has major economic interests in undersea territory rich in oil, natural gas, minerals and sea life to which it has sovereign rights under the law of the sea as reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention. Article 76 of UNCLOS, which the US recognizes as reflecting customary international law, provides the roadmap for determining the limits of the ECS, and by following its requirements the US has been able to declare its rights to approximately one million square kilometers of subsea territory – an area about twice the size of California or nearly half the size of the Louisiana Purchase. The technology for exploiting these resources is limited today, but in the future that may change, and the US is thus able to protect future economic opportunities. And in a world where climate change and environmental protection are at the forefront of policy interests, the US also has the ability to take a policy decision to conserve these areas, as well as to advance study and scientific exploration in deep sea regions that are not well mapped or understood.

The materials issued by the State Department along with the announcement make clear the Biden Administration’s position in favor of ratification of UNCLOS, but this Administration and others understood that the United States did not have to be a party in order to protect its rights. Indeed, given that as many as 75 countries have delineated their ECS limits, it was necessary for the United States to take action in the near term. That is particularly the case in the context of the Arctic where the other four states surrounding the Arctic Ocean (Canada, Denmark (for Greenland), Norway and Russia) have each made at least one submission to the CLCS.

2. The announcement involved a major effort by the US Government

The US determination of ECS limits is grounded in complicated and expensive collection and evaluation of scientific data from bathymetric and seismic surveys needed to meet the requirements of Article 76, and involved many years of work by 14 federal agencies led by the US Extended Continental Shelf Task Force, chaired by the State Department. Data collection began in 2003, and was supported by an ECS Project Office established in Boulder, Colorado in 2014. This project required the largest offshore mapping effort ever undertaken by the United States, involved more than 40 surveys and cost tens of millions of dollars.

The State Department has released only the Executive Summary of a much larger set of non-public documents that would at a later stage be made available to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) which was formed under Article 76 to undertake scientific and technical review.

3. Not just about the Arctic, but major implications there

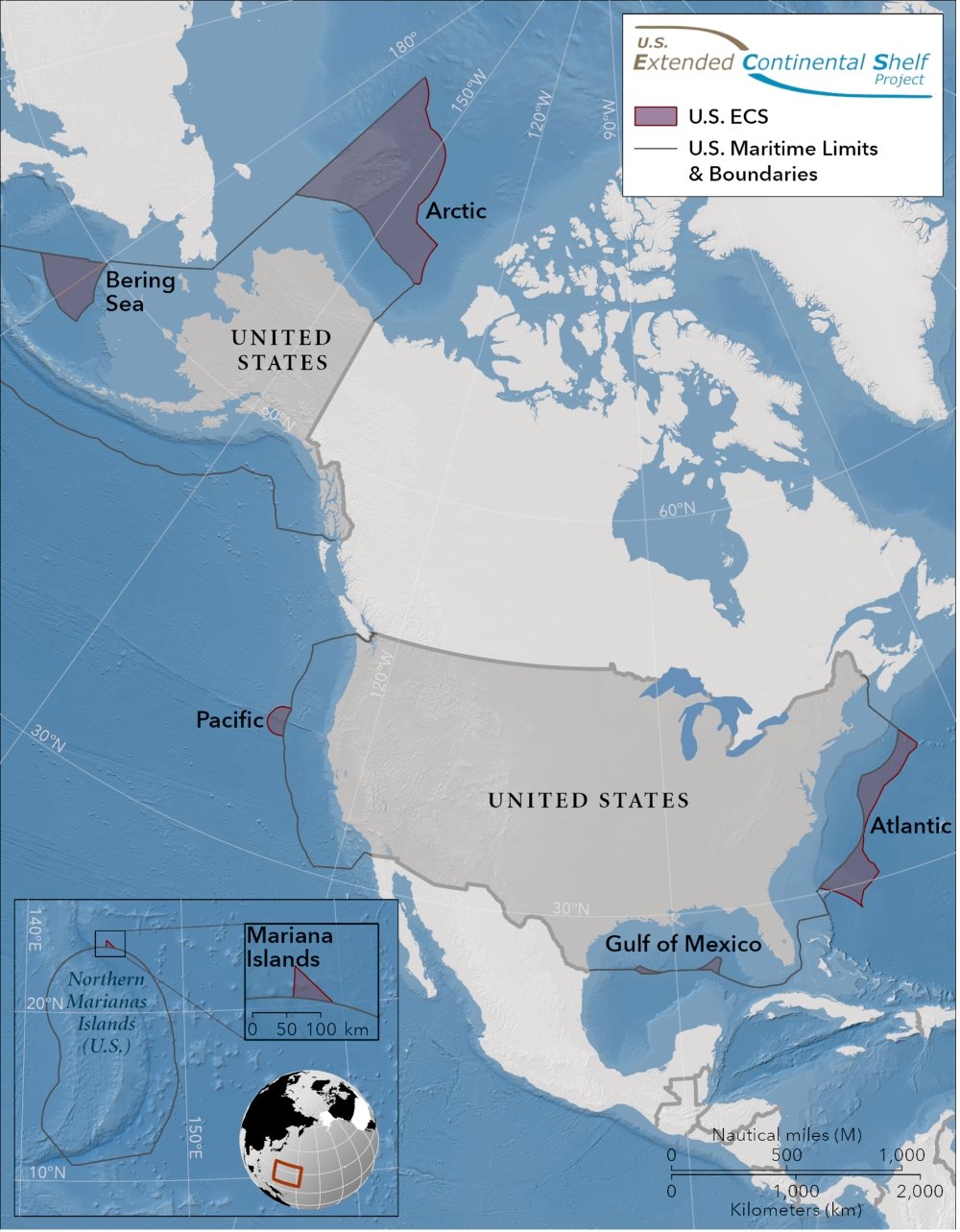

The US announcement has important implications for securing US territorial rights in the Arctic, which have been analyzed elsewhere. Indeed, the largest area of US ECS is in the Arctic. However, the United States has ECS in six other regions: Atlantic (east coast), Bering Sea, Pacific (west coast), Mariana Islands, and two areas in the Gulf of Mexico. All of these are detailed in the Executive Summary and shown below.

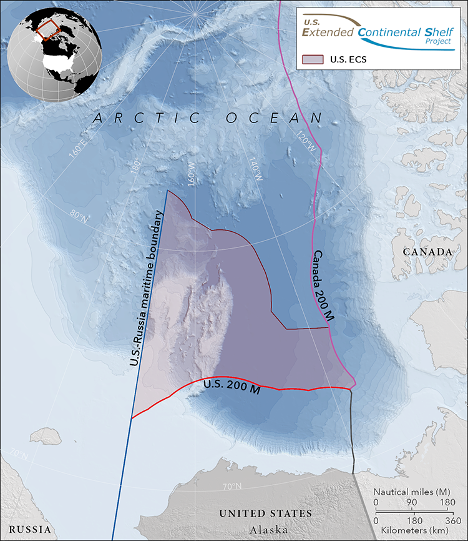

The extended continental shelf of the United States in the Arctic extends north to a distance of 350 nautical miles (in the east) and more than 680 nautical miles (in the west) from the territorial sea baselines of the United States.

By defining its ECS limits in the Arctic, the United States carries out its Arctic policy established in the National Strategy for the Arctic Region (October 2022) which provided that the United States “will delineate the outer limits of the US continental shelf in accordance with international law as reflected in [UNCLOS]”.

It is worth noting that the United States does not claim that its Arctic ECS reaches the North Pole, by contrast to other Arctic coastal states. That is because the science did not support drawing limits that far north.

4. There are international implications

The declaration of ECS limits by all five of the Arctic littoral states now makes it abundantly clear that the vast majority of Arctic seabed is within the national jurisdiction of one of the five states. Only a small section is likely to be international seabed, under the jurisdiction of the International Seabed Authority. Areas of overlap will require negotiations among relevant states. It is now quite clear that rights to Arctic ECS are being addressed in an orderly manner through procedures identified in UNCLOS; there is no helter-skelter scramble for resources which the media sometimes portrays.

Indeed, Arctic ECS has been the subject of cooperative discussion among the five Arctic Ocean coastal states, which have known all along that there would be ECS overlaps. All five states had been meeting and working together cooperatively until the Russian invasion of Ukraine; now these states minus Russia have continued their cooperation post-invasion.

As the materials accompanying the US announcement make clear, the US ECS partially overlaps with ECS areas of Canada, The Bahamas, and Japan. In these areas, the United States and its neighbors will need to establish maritime boundaries in the future. In other areas, the United States has already established ECS boundaries with its neighbors, including with Cuba, Mexico, and Russia.

There is no need for a future negotiation with Russia because each country has delineated the outer limit of its continental shelf consistent with the boundary established in 1990 in the Agreement between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Maritime Boundary, which has been provisionally applied by agreement between the two countries. (The Russian Federation is the successor of the USSR with respect to the 1990 Agreement and the agreement to provisionally apply it.) Although the US Senate has given advice and consent to ratification of this Agreement, the Duma has not, and thus it has not entered into force. Nevertheless, both countries have found it their respective interests to apply the 1990 Agreement, including in this ECS context.

5. The announcement involved a key decision on whether to make a submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf

In order to protect its ECS rights and make a persuasive case to the international community, the United States had to either make a submission to the CLCS or make a unilateral announcement. It chose the latter course.

The key phrasing used by the Department of State in the announcement is: “The United States has prepared a submission to the CLCS. The Department of State will file it with the Commission when the United States joins the Law of the Sea Convention. The United States is also open to filing its submission with the Commission as a non-Party to the Convention.”

Although the US had strong legal arguments under the language of Article 76 that it could make a submission even as a non-party to UNCLOS, inevitably some countries would have issued protests claiming that a non-party does not have such a right. In addition, some countries might remain silent on the issue, which also could create confusion.

As coastal states have an inherent right to ECS not requiring a submission to or action by the CLCS, the action by the United States is sufficient for now to protect its rights. However, in the longer term, the best form of protection will be if the limits are deemed “final and binding,” which will occur if the United States establishes its limits on the basis of the CLCS’s recommendations following a submission.

It is worth noting that given the huge backlog of submissions, which are reviewed in the order received, even if the United States were to make a submission, the review would not take place for decades.

Author

Former Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary for Oceans and Fisheries and Director for Ocean and Polar Affairs, US Department of State

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Fulbright Arctic Initiative IV Scholar at the Polar Institute

Trump 2.0’s Arctic Opportunity: Thawing Frozen Dialogue