This article is part of a series of papers that resulted in the new report:

First Resort: An Agenda for the United States and the European Union

Joe Biden’s election as President of the United States presents an opportunity to renew the transatlantic relationship, and particularly the transatlantic economic relationship, after four rocky years.

The U.S. and Europe cannot of course simply go back and pick up the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations where they left off when Mr. Biden was Vice President, on January 20, 2017. Those negotiations had run into obstacles of their own, some self-inflicted (the miscommunication on tariff offers in the opening months had lasting consequences), some legitimate (concerns over regulatory protections) and some illegitimately fanned (settling investment disputes, ISDS). TTIP might have been completed under a Hillary Clinton presidency, but getting EU member state approval and ratification would have been problematic, as the tortured path of the EU-Canada trade agreement CETA shows.

And yet -- TTIP was there for a reason: to promote economic growth and to bind the United States and European Union more closely together. Rather than reject it outright (as many in the transatlantic trade community now do), the right lessons should be drawn and should inform specific steps and ambitions for the next four years. An ambitious agenda would see the two sides:

- rebuild the narrative for fair trade;

- develop a strategic approach to their economic relationship, bilaterally and in the world;

- adopt a truly ambitious vision for where they want to go, while accepting that it will take time to get there;

- resolve the key problems besetting the trade relationship today, including on national security tariffs, Boeing-Airbus, data protection, digital services taxes, and climate-related border measures;

- understand that regulatory differences can only be settled outside the trade relationship;

- negotiate a broad North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement that focuses on market access, in a way that allows true progress on agricultural trade, digital services, government procurement and investment; and

- address global economic issues, including in particular WTO reform and China (and, in that latter context, national security controls for trade and investment in emerging and foundational technologies).

The United States and Europe can resolve the disputes between them, as detailed below, and can work as partners to address broader global issues. They can only accomplish the former, however, if they have a strategic and ambitious vision of their partnership; anything less will dissolve into bickering. And they can only make a difference at the global level if they reach accommodation bilaterally; any thought that the two can together lead on the international level after sweeping bilateral issues under the rug is an illusion. Summoning the political will for a true partnership may not be easy, but the consequence of not doing so will assuredly be worse.

Rebuild the Narrative for Trade

The United States and the European Union must begin by reconstructing the narrative for open trade. The global trading system has delivered great benefits over the past 75 years – billions of people have been lifted out of poverty, sickness and despair, largely by export-oriented growth strategies. But while workers in the West benefited enormously for the first half of this period, they have seen little progress since as the benefits of trade spread instead to the developing countries. They are accordingly now skeptical of globalization, technology and trade.

To address this, governments in the industrialized world must invest substantially more in programs to help workers adjust to change, even as they also promote programs to enhance their firms’ competitiveness. As part of a reimagined effort, the transatlantic partners should also launch an Alliance for Fair Open Trade. “Fair” rather than “free,” which is too closely associated with a pro-corporate and non-regulatory approach. Instead, this alliance should advocate broadly, including in the WTO, that countries should play by the same international rules, while recognizing that domestic conditions will vary.

Inject Strategy into Transatlantic Trade

The European Commission has proposed a New Transatlantic Agenda for Global Change, and specifically a Transatlantic Trade and Technology Council. Properly done, this could be useful, especially if it brings strategic thinking back into the economic relationship. This was the original vision for the Transatlantic Economic Council (TEC), which had an in-depth principals-only discussion of China at its first meeting in November 2007 that led to a significant increase in transatlantic cooperation on China. Unfortunately, the TEC then degenerated into a test of wills over chlorinated chicken. The new Council should include the economic policy principals on both sides, chaired at the Vice President level, with only strategic issues -- bilateral and with third countries -- on its agenda.

Adopt an Ambitious Vision

Beyond this new forum, any discussion of ways to enhance the transatlantic trade and investment relationship must begin with a vision of where the two sides want to go. The minimalist vision of just fixing what many see as the “problems of Trump’s trade policy” is insufficient as it ignores that many of the problems predate Trump, that his one actual “de novo” blow to transatlantic ties (section 232 sanctions on steel and aluminum) is relatively minor, and that Europe too has contributed to the problems in the bilateral relationship.

TTIP offered a vision – a barrier-free transatlantic marketplace. This is a reasonable and fitting vision for large well-developed democracies that share – uniquely – an investment-based economic relationship. Not least as they must acknowledge that their global leadership is now being seriously challenged, internally by questions about global leadership, and externally by China. The TTIP vision, properly implemented, would have addressed both.

But the TTIP vision was unnecessarily oversold as a regulatory merger. European consumers rebelled at what they perceived as Big American Business undermining their social protections, including through investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). But TTIP was never going to allow one side force regulatory change on the other, as American businesses also rebelled against any approach that implied possibly taking on “burdensome” European rules. The TTIP vision of integrating the transatlantic economy can only be kept if the two sides underscore that their respective regulatory norms cannot and will not be weakened in a trade agreement, but will continue to reflect their own democratic choices, under the oversight of their democratically-elected representatives.

Resolve Today’s Problems

If the two sides can create a narrative for fair trade, think strategically about their economic relationship, and have a vision for where they would like to go, many of today’s transatlantic trade frictions will be easier to resolve. Without that renewed narrative, strategy and vision, resolution of today’s problems will likely elude them.

Today’s major bilateral problems are the Trump national security (Sec. 232) tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, and the Airbus-Boeing tariffs (which also implicates to agricultural trade). But those problems also include, on the EU side, data protection, the digital services tax and carbon border adjustment.

Steel and Aluminum: The Trump administration’s decision to use national security reasons for restricting imports of steel and aluminum under Section 232 is both a systemic and a particular problem. National security was former U.S. Trade Representative Lighthizer’s last legal hook to address problems he long felt these industries face. Doing so was a huge mistake that may forever undermine the US arguments for a self-judging exception for national security, but the EU (and others) should understand the point of the measure was to bring the domestic industry back to profitability, not to stop imports from friendly countries as such.

Mr. Biden will not be able to immediately eliminate the tariffs without appearing to attack the workers in these politically iconic industries, so he could instead convert the steel and aluminum tariffs to a short-term safeguard action, phasing out over two years. If he does, the EU should accept this, especially if the Administration agrees to drop the other less politically-important 232 cases the Trump administration started (autos, uranium, transformers, cranes, etc).

Airbus-Boeing: A long-running battle that the Europeans inexplicably chose to make worse just after Mr. Biden was elected in November, when they levied punitive tariffs on $4 billion of U.S. exports after a WTO decision on America’s subsidization of Boeing, rather than wait to see if the new Administration would be willing to negotiate away the $7.5 billion in tariffs the U.S. had imposed on Europe a year earlier because of EU subsidization of Airbus. Thankfully, Mr. Lighthizer did not escalate this as much as he could have, given that Washington state had legally ended the last program that benefited Boeing. (Although he did in January further up the retaliation on French and German goods by mirroring the EU’s decision to use lower 2020 trade levels as a basis for the retaliation, which means a wider range of products are affected.) Both sides know the two companies need them to resolve this dispute and concentrate on the upcoming China threat. And both sides know the solution – Airbus will have to repay at least some of the outstanding A380 and other loans, but the U.S. will have to accept that the repayment terms cannot be confiscatory. This will be easier to agree under Biden, as Lighthizer was using the Airbus case to put pressure on European agricultural trade, as discussed below; a plan for resolving those is accordingly needed as well.

Data Protection/Privacy Shield: The issue of data protection goes far beyond digital issues and is directly relevant to trade. The European Court of Justice’s decision in July to invalidate the U.S.-EU Privacy Shield agreement under the so-called Schrems II judgement has pushed data protection to its (illogical) extreme and threatens all economic (and social) discourse between the US and the EU, never mind the EU and the rest of the world (save Japan, the only country with an up to date adequacy decision). It can only be corrected by another ECJ judgement that explicitly brings “proportionality” considerations into what the Court has said is a fundamental right. That is to say, just because a government (U.S., Russia, China, Israel, Turkey, etc.) can access data transmissions to its territory, prohibiting all data transmissions that country – as the EU data protection laws nominally require – would be ridiculous; a rule of reason, exemplified in the EU Commission’s new draft “Standard Contract Clause,” should apply instead. This process of re-litigating Schrems II will not be easy, but it is now an EU rather than transatlantic problem.

Digital Services Tax: This too is a trade issue, and not just because of the U.S. government’s threatened responses against the French, UK and other countries that may adopt a DST. That an importing country is arrogating to itself the right to levy a corporate tax on revenues/earnings of an exporter that may have no presence at all in the importing country (e.g., AirBNB) should be an immense concern to Europe’s traditional exporting companies, even if the companies that are the focus of this particular tax export digitally-enabled services.

Carbon Border Adjustment: Again, relevant here as it will raise the price of imports. This issue could fall away, as the United States becomes a less-easy target now that it has rejoined the Paris Climate Agreement. And the US and EU may well have precisely aligned concerns afterward, if both seek to become carbon-neutral by 2050. But they will take different approaches, with the US more focused on regulatory and tax measures rather than emissions reduction/trading. The EU would be seriously mistaken to try to levy a carbon border tax on the U.S. just because it uses different mechanisms. The two should just pre-emptively bury this hatchet, especially as Resources for the Future in an extensive study underscores that the only WTO-legal approach is an (indirect) carbon tax with a border adjustment, like the VAT – an approach that may come closer to that adopted by the Biden team.

With a narrative, vision, strategy and having swept old issues out of the way, the two sides can free themselves up for thinking bigger.

Treat Regulatory Cooperation Separately

If the two sides keep the vision of an integrated transatlantic economy but learn the TTIP lesson, they will treat trade (market access) and regulatory issues separately.

As discussed below, the two sides could and should negotiate a free trade agreement (FTA). BUT the TTIP debate showed that regulatory issues must be outside this agreement. A transatlantic FTA can speak generally about good regulation and can promote novel modes of cooperation (see standards, below). But in high-income democracies, the public needs to be certain that regulatory protections adopted through democratic processes are not up for negotiation. Regulators, overseen by democratically elected representatives, can be encouraged to reach agreements with transatlantic counterparts when levels of protection are similar, as such agreements improve their efficiency and effectiveness in protecting their own citizens, as President Obama’s Executive Order on international regulatory cooperation stresses.

But this process – which was going on between the US and EU with some success for over 20 years before it almost stalled with TTIP -- can and should be separate from any FTA negotiations, and from trade negotiators. Instead, this agenda should be overseen by the existing High Level Regulatory Cooperation Forum, although it should act much more like the Regulatory Cooperation Councils discussed in the Executive Order noted above.

Leap toward a North Atlantic FTA

While Mr. Biden may want to shy away from new trade deals, he also needs to address the depressed domestic economy. Integrating the transatlantic economy offers a stimulus, and even for Democratic progressives transatlantic trade can be free because Europe’s high labor and environmental standards mean it is already fair. Further, the global competitiveness of European and American firms (and thus the welfare of their workers) in the face of Chinese competition demands reducing barriers to trade between their operations on both sides of the Atlantic.

As such, Mr. Biden should offer to conclude a North Atlantic FTA focused on market access issues rather than regulation and rules. One that recognizes the broader patterns of trade and investment, and thus includes the U.S.-Mexico-Canada agreement, the EEA, the (Brexited) UK and Switzerland, with full cross-cumulation in the rules of origin. (Regulatory issues, as noted above, would not be included; as regulatory cooperation depends on the regulators trusting one another, they can only be handled bilaterally in any event.) This could be supplemented by enhanced R&D cooperation and more collaboration on rules for new technology.

With Agriculture, but not Food Safety

Agriculture is the most contentious area in transatlantic trade, and the suggested separation between market access and regulatory protection must apply here as well for there to be any chance of resolving these problems.

Market access issues should be included in the FTA, regardless of what one thinks President Juncker agreed with Mr. Trump in July 2018 or supposed trade-offs with government procurement. (The oft-cited EU linkage between agriculture and government procurement implies the EU would give up on food safety considerations if given better procurement access; it would not and could not do so.) In this area, both sides understood during the TTIP negotiations that the other would not be able to eliminate tariffs and quotas on all agro-food products, but they generally believed 95-97% of all those products could be liberalized – not least as one third of the U.S. and EU agro-food tariff lines are already at zero anyway.

But the SPS issues – GMOs, chlorinated chicken, beef hormones – can and must be handled separately, clearly outside the trade talks and only by those responsible for food/plant safety. The U.S. side may argue that this makes market access liberalization pointless, as the main EU barriers to U.S. food and commodity exports are regulatory. There is truth in this, but it neglects that the EU has similar complaints about many U.S. regulatory requirements that block European agro-food exports.

Which suggests taking a novel approach to these issues: rather than discuss each individually, look at them together and divide them into four groups:

- the few areas where the regulators differ on their scientific assessment of the safety of the food;

- those where they don’t argue about whether the food is safe, but require different methodologies to prove this;

- those where the regulators (ostensibly) lack resources to inspect the safety of the other side’s food-producing facilities; and

- those where politics makes a decision unlikely, even if the regulators don’t disagree on safety.

On the first, the two clearly should prioritize cooperation, as regulators on both sides do not want their citizens consuming foods that may be unsafe. The second and third groups looked at together should provide numerous opportunities for win-win actions. The last group should be put aside.

The EU’s GMO regulation, which has such a major impact on U.S. commodity exports to Europe, is normally considered in the last “too-difficult” category. But these problems can be resolved. One reason for this: previous methods of transgenetic modification are giving way to new ways to control gene expression within a plant or animal. This approach is less objectionable, and indeed many EU stakeholders are trying to find a way to get around the recent ECJ ruling that indicated the new technology also falls under the old GM foods directive. Beyond that, in this area the US should give up on trying to force European member states to accept biotech varieties for cultivation (seeds); European farmers need to fight this battle. The U.S. focus instead should be on facilitating EU Commission authorizations for import and use of GM varieties. Here, the United States should acknowledge that the EU has a valid scientific assessment process (having approved about 90 varieties, most recently in October 2020), although the two could discuss further such things as evaluation of GMOs that have multiple novel traits (“stacked” GMOs). The two sides should then map the differences between the varieties used commercially in the United States and those the EU permits for import and use, and agree to a process to expedite European Food Safety Agency evaluations in the commodities where these asymmetries are smaller (e.g., cotton, rice, rapeseed) to facilitate exports commodity by commodity. While this approach would take time (longest for corn, where the differences are greatest), it would arguably be faster than the impasse we face.

Build an SME Standards Bridge

For industrial products, the FTA should include an SME Standards Bridge. As a general regulatory matter, each side would agree to recognize standards used by the other side where those standards meet existing regulatory requirements. This would allow small European firms that manufacture to certain “European Norms” to claim that their products meet U.S. safety levels, and of course vice versa.

As a matter of law and practice, this is already allowed in the United States. But while the U.S. recognizes many EU member state standards as conforming to U.S. requirements, fewer EU level standards (“European Norms, or ENs) have this status, in part as they came later in time. An active work program should be developed to address this. On the other side of the Atlantic, EU law allows individual products built to non-EU standards to demonstrate they meet EU safety requirements, and so the EU theoretically could accept that all products built the same way also meet those requirements. EU officials, however, are reluctant to recognize a second non-EU standard as providing a presumption of conformity because they fear member states would begin to insist on using their own standards, thereby weakening the Single Market. This concern is overdrawn, however, since member states would have already agreed to a single European Norm, and no European firm, having adopted that standard, would want to switch to another. Again, such a Standards Bridge would do more for SMEs on both sides of the Atlantic than almost anything else in an FTA.

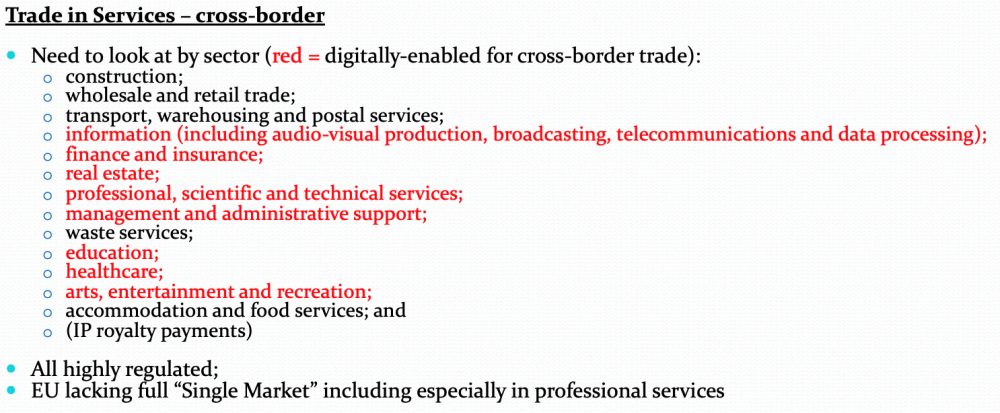

Cover services, especially digitally-enabled, but beware

Any EU-US trade agreement must cover services, with more liberalization than in the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). At a minimum, each side should promise as a general rule to allow service providers of the other side to operate under the same rules as their own firms (national treatment), with any exceptions to this clearly spelled out.

This “negative list” approach includes, of course, digitally-enabled cross-border trade in services. When GATS started in 1995, most services could only be traded through a physical presence: either through an investment in another country, or by the movement of the service supplier or the consumer (e.g., as a tourist). The internet of course has changed all that, and many services can now be delivered digitally across borders, as the wide-range of services listed in red above attests. Indeed, of the four ways services are delivered, digitally-enabled services trade is now the most important to deal with in the US-EU context, where investment and movement of service consumers/providers function well.

This implies any FTA must have strong digital policy disciplines. Alas, this could be contentious between the US and EU. This is partly due to the privacy issue discussed above, but reflects as well growing EU concerns about non-European providers of cloud services, the need to promote data-sharing, and the market power of some U.S. platforms. But a growing number in the United States share these concerns, which can best be addressed through cooperation by competition policy authorities, whereas the FTA can instead discipline things like unjustified data localization requirements or demands to divulge source code, on which the two sides agree.

Regulation is also a major issue in cross-border services trade. Each of the sub-sectors noted above is highly regulated, and it is likely that much of the trade now going on in areas like healthcare or education is illegal, strictly speaking. But consumers clearly benefit, and so far there have been few complaints. That said, this needs to be seriously addressed in the regulatory forum process noted above. As many of these services are regulated at the local level, the Regulatory Cooperation Forum will need to accommodate this as well.

Other Market Access Issues

Government procurement needn’t get worse, as everyone fears, for again there’s little transatlantic social dumping. As noted above, the trade-off here is not cross-sectoral with agriculture, but rather within procurement. Specifically, the EU argues that it is nominally much more open that the United States on government procurement, while the U.S. argues that European firms actually win lots of U.S. government contracts, whereas U.S. firms don’t do well in Europe. Mr. Biden’s recent announcement to further tighten the application of U.S. procurement law doesn’t help here. But his arguments point both to the need to use taxpayer money well, and to avoid “social dumping” by firms not subject to U.S. level labor and environmental law. The EU does not fall into this category, so the U.S. can afford to provide enhanced de jure access for European exporters in exchange for better de facto access to EU procurement markets for American workers, this last perhaps enforced through an ombudsman mechanism.

And on investment, the two sides have far and away the deepest possible relations with nearly $6 trillion in foreign direct investment between them. They can easily agree to provide the three substantive protections seen in most investment agreements (national treatment on establishment and operation, with any exceptions spelled out; expropriation in accordance with international law; and free transfers of funds related to the investment). These are not controversial between them. But they should agree to remove investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), which nearly brought TTIP to its knees. ISDS is normally advantageous as it removes governments from the dispute process, but it arguably isn’t needed in either the United States or European Union.

An FTA focused as described above on traditional market access issues, while handling regulatory issues separately, should be technically easy to conclude, would have a notable economic impact and should be politically acceptable as transatlantic trade is already basically fair, and so can more easily be free.

An Ambitious Third-Country Agenda

If the two sides can rebuild the sense of why they’re internationally engaged, can bring a strategic approach to their deliberations, can establish and begin to execute on a joint vision of what they want to achieve (and why), and can sweep away the niggling issues, they should be set to build an ambitious agenda for joint action beyond their bilateral relationship.

It is, however, debatable that they can tackle things like WTO reform and the China challenge without these other steps, for if they have not agreed about the relationship they want to have between them, they will not be able to work together on other issues.

Invigorate and reform the WTO

A Biden Administration will be strongly predisposed to support the WTO and the international rule of law that it represents. Today’s differences over the next WTO Director-General, where the Trump administration was the sole opponent of the otherwise agreed candidate, should be easily resolved. But a key problem for the United States that predates Mr. Trump is the series of Appellate Body decisions circumscribing the use of anti-dumping and countervailing duty measures in response to unfair trade practices. The EU seems disposed to be helpful on this substantive point as well as the many associated procedural ones, and the two sides should agree to press for these to be addressed at the 2021 WTO Ministerial.

This is additionally necessary as it relates to China, as discussed below. Further liberalization under the WTO is unlikely absent resolving the China issues, as India and a long list of other developing countries are unlikely to give China access to their markets as long as China’s economy is so distorted toward export-driven growth.

Build a Coalition to Promote China’s Reform

The EU has long shared US concerns about Chinese economic policy, as was highlighted in the cooperation that followed the first TEC meeting in 2007 and as underscored in DG Trade’s Staff Working Document demonstrating that China does not qualify as a market economy. The Trump administration neglected the EU, however, as it pursued its own agenda (despite the US-EU-Japan “level playing field” exercise on industrial subsidies), largely because it believed the EU would not be tough enough on Beijing. That is demonstrably not so. Despite the EU’s (unwise) decision to conclude the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment in December, the Biden administration will clearly need to work more closely with Europe on the China challenge.

The EU side will want a Biden administration to take a more measured and less bellicose approach to Beijing. It will want Biden to discontinue at least Trump’s escalatory tariffs on China (those above the original $50 billion imposed in response to China’s forced technology acquisition practices), and to renounce the bilateral purchase commitments in Trump’s January 2020 Phase I agreement. Neither will be easy to do absent a strong signal from Beijing that it is willing to talk seriously about domestic economic reforms to address the distortions the PRC’s export-oriented growth strategy have caused, domestically and in/to the global economy. Brussels can help here, and can help specifically to build the coalition of middle-income countries needed to support a comprehensive WTO case based on China’s WTO accession protocol (which will help give Beijing cover for politically tough reforms it must undertake).

Focus on Emerging Technology and National Security Controls

But there is a major security dimension to the China discussion as well. The EU’s recent agreement on the recast of its Dual-Use Export Controls Regulation presents an important opportunity for the two sides to establish an intensive dialogue on dual-use foundational and emerging technologies, with necessary intelligence-sharing capabilities to inform both export control and FDI screening activities.

The United States and the European Union have an opportunity with the new Biden Administration setting up in Washington. They can develop a true partnership with a real vision and an actual strategy. They could do a lot together, which would have immense economic and geopolitical benefits – including through joint leadership in the many international fora that are crying out for it -- the WTO, OECD, G-7, G-20, the international financial institutions, international standard setting bodies, and elsewhere.

But this will not happen merely because politicians on both sides of the Atlantic proclaim that the United States and Europe “should” cooperate, because they “share common values.”

Rather, the two sides need to choose -- actively choose -- to take advantage of this opportunity. Because they see it in their respective interests. And they will have to work hard to make it work, as in any relationship, for there will be political costs to bear.

The decisions both sides have taken since November do not bode well. The Biden Administration is showing no desire to remove the punitive tariffs the Trump administration placed on global trade, with Europe or elsewhere. Indeed, it’s rather increasing barriers to government procurement, and using the same belligerent tone toward China. The EU for its part has inexplicably intensified the struggle over Airbus-Boeing, needlessly pushed forward the investment agreement with China, and raised the volume on “strategic autonomy” – not least from U.S. information technology companies.

All of which underscores that simply “muddling through” is not an option. The choice instead is between actively deciding to improve the transatlantic economic relationship, or to let it worsen.

That choice is not just an economic one. It will have geopolitical consequences.

We can only hope our political leaders choose wisely.

Author

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

360° View of How Southeast Asia Can Attract More FDI in Chips and AI