Bilateral Water Management: Water Sharing between the US and Mexico along the Border

Since the early 19th century, the United States and Mexico have worked to develop a bilateral framework for the equitable management and distribution of water. Even with the passage of time, water management remains a key topic in the bilateral relationship. In October 2020, a five-year water sharing cycle came to an end, sparking interest and potential conflict over the issue of water debts. Though an amicable agreement was reached without too much delay, this primer aims to explain the history behind the issue of cross-border water management.

Wilson Center

Of the many rivers that cross the border lands shared by the United States and Mexico, the Colorado River and the Rio Grande/Bravo stand out as giants. Alone, these two rivers constitute two-thirds of the border and, since the early 19th century, both countries have worked to develop a bilateral framework for the equitable management and distribution of water. Even with the passage of time, water management remains a key topic in the bilateral relationship, particularly as the impacts of climate change, as embodied in this region by severe droughts, become more visible, and as economic and demographic changes along the border region become increasingly apparent. In October 2020, a five-year water sharing cycle came to an end, sparking interest and potential conflict over the issue of water debts. Though an amicable agreement was reached without too much delay, this primer aims to explain the history behind the issue of cross-border water management.

Historical background:

Surface waters along the U.S.-Mexican border have been managed via the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1848 and the 1906 Convention between the United States and Mexico for the Equitable Distribution of the Waters of the Rio Bravo/Grande. Though originally quite narrow in scope, the 1906 Convention laid the foundation for the most well-known water management treaty, the Treaty between Mexico and the United States for the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers and of the Rio Grande,more commonly referred as the 1944 Water Treaty. This treaty developed water allocations for Mexico and the United States and established the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) / Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas (CILA).

While the IBWC’s origins can be traced back to 1889, the 1944 Treaty transformed the commission and expanded its power. Tasked with addressing conflicts related to border management and water sharing, the IBWC’s most important function is serving as the primary arbiter in binational debates regarding water management. In fact, a 2005 report found that the IBWC has resolved most of the border water disputes that have emerged since the treaty’s adoption in 1944. The 1944 Treaty allocates significant power to the IBWC, most notably through the ability to develop minutes, or legislation regarding treaty interpretation and implementation. Though minutes are direct extensions of the treaty and are considered binding agreements, they are unique in that they ensure flexibility for treaty adherence by permitting appropriate adjustments as necessary. They play a critical role in promoting bilateral cooperation and have addressed a wide variety of issues in the past, such as: “operation and maintenance of cross-border sanitation plants, water conveyance during droughts, construction of dams, and water salinity problems.” Since the treaty’s ratification in 1944, 179 minutes have been ratified.

Though the IBWC is an international body, both the US and Mexico have separate divisions of the IBWC. Each country has its own commissioner, principal engineers, legal advisers, and foreign affairs secretary. The US IBWC is headquartered in El Paso, Texas and is considered a federal government agency under the oversight of the Department of State, whereas the Mexican IBWC is headquartered in Ciudad Juárez. In the US, decisions on whether or not to adopt a minute is often left to the discretion of the Secretary of State, without congressional involvement.

1944 Treaty Stipulations & Delivery Requirements:

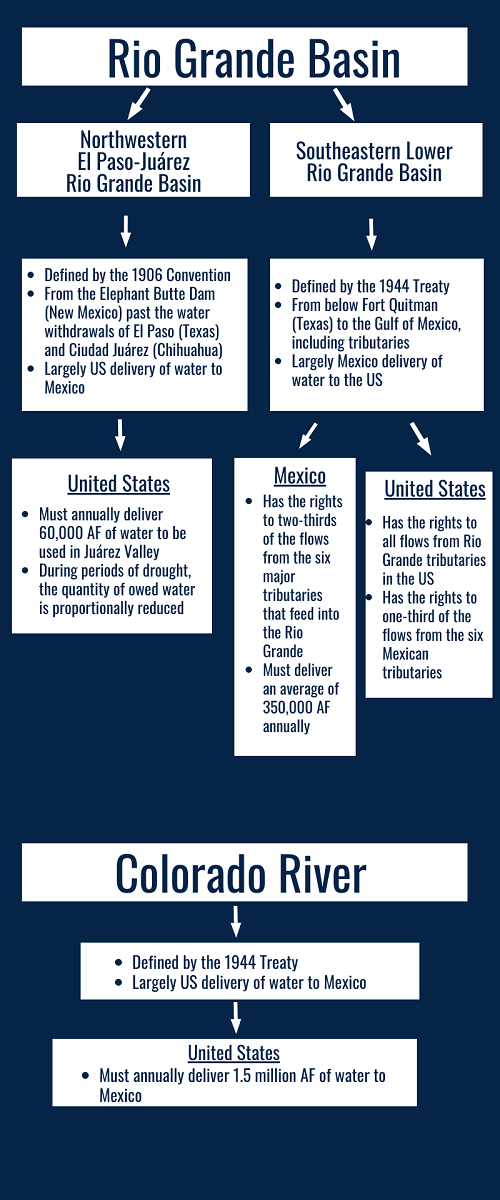

Included in the 1944 Water Treaty are policies regulating water storage, hydropower, sanitation and flooding precautions. However, the most significant power enumerated in the treaty involves the regulation of water from the Colorado River and the Rio Grande.

The Colorado River flows through seven states in the US (Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) until it reaches Mexico. A whopping 97% of the river’s basin is located on U.S. territory. At the time of the Treaty’s initial implementation, the water flow of the Colorado River was estimated to be 16.8 million acre-feet (AF), but recent reports indicate that the current average flow is closer to 14.4 million AF per year. According to the 1944 Treaty, the United States is required to give Mexico 1.5 million AF of water per year, which amounts to 10% of the annual flow of the river.

Though the water for this treaty comes from all over Northern Mexico, the state of Chihuahua carries a significant burden because one of the state’s main rivers, Río Conchos, is a primary tributary of the Rio Grande. The Río Conchos has been the most important tributary for the Southeastern lower Rio Grande basin, as it has historically contributed 70% of the total flow owed to the US. However, since the 1990’s, its flow has substantially decreased and it now contributes around 40% of the total flow (Carter). From the Northwestern portion of the Rio Grande, the United States is required to deliver 60,000 AF to Mexico, which is to be used in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Though the Rio Grande appears to be a continuous basin, it operates as two distinct binational basins: the Northwestern El Paso/Juárez Rio Grande basin and the Southeastern lower Rio Grande basin (including its tributaries). Whereas the northwestern portion of the basin is governed by the 1906 Convention, deliveries from the southeastern basin are regulated by the 1944 Treaty. According to binational agreements, Mexico retains the right to two-thirds of the flow of the water from the six major tributaries that feed into the Rio Grande on the Mexican side. The US is entitled to all water flows from the Rio Grande tributaries located on U.S. territory and to one-third of the water from the six tributaries located on Mexican territory. Mexico must deliver an average of 350,000 AF of water per year (measured in five-year cycles) to the US.

Failure to Meet Water Delivery Requirements:

Under certain conditions elaborated in the 1944 Treaty, water deliveries can be postponed. For example, cases of “extraordinary drought or serious accident” are considered viable excuses for failure to meet water delivery requirements. What constitutes “extraordinary drought or serious accident” remains vague as the term is not defined in the 1944 Treaty and has not yet been defined by a minute. The repayment of water debts must follow the guidelines established in the 1944 Treaty.

Should Mexico fail to fulfill its water obligation to the US due to extreme drought, it must repay its water debt during the next five-year cycle. Minute 234 stipulates that neither country may accrue a shortfall for two consecutive five-year cycles. The minute also specifies the sources that can be utilized to repay water debts: excess water from tributaries, a portion of the allotment from tributaries, and the transfer of water stored in international reservoirs, such as the Amistad and Falcon dams.

On the other hand, if the US is unable to deliver water from the Colorado River to Mexico due to extreme drought, the amount of water due will be proportionally reduced to reflect consumptive uses in the US, according to Article 10 of the Treaty. It is important to note that the Treaty does not specify measures for noncompliance. In the event that conflict arises over failure to meet water delivery requirements as established by the 1944 Treaty, such disputes should be resolved by the IBWC commissioners. If unresolved, disputes can be addressed via diplomatic means and the development of minutes.

Water Sharing in the Recent Past:

From 1944 until 1994, Mexico reliably delivered its portion of water to the US, but a drought lasting from 1994 until 2003 significantly impacted Mexico’s ability to transfer water, forcing the country to amass a water debt through two five-year cycles. This gained significant media and political attention, particularly in the Southeastern lower Rio Grande basin. Through a multifaceted approach including improved water efficiency, negotiation of new minutes, and presidential intervention, the conflict was resolved and Mexico successfully paid off its debt. Increased water levels resulting from hurricanes permitted Mexico to pay off its water debt in 2005.

A decade later, in 2015, Mexico again fell short on its deliveries early into the five-year cycle. This resulted in an overall shortfall of 216,250 AF or 15% of the total water owed for the 2010-2015 cycle. In January 2016, a few months after the cycle’s end, Mexico fully paid off its water debt.

The 2015-2020 Water Cycle:

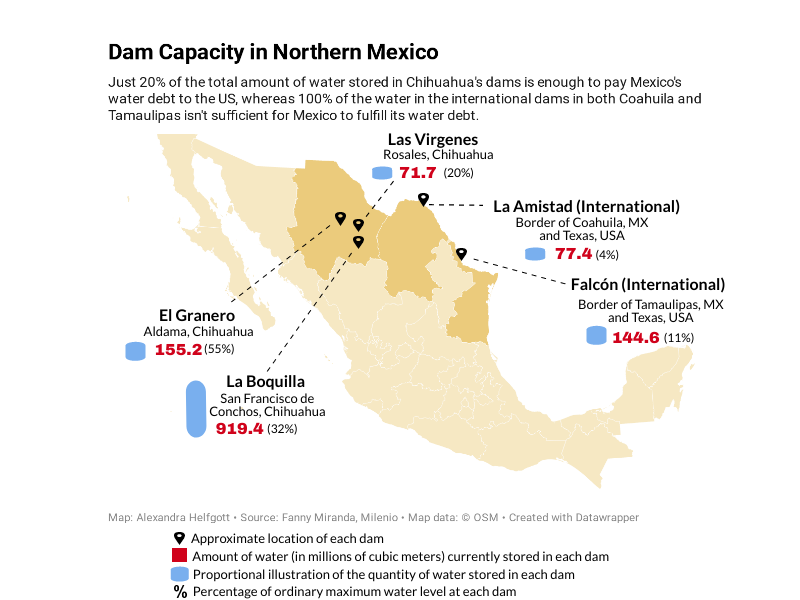

Deficiencies in water deliveries early in the following cycle (2015-2020)led many to believe that Mexico would once again fall behind on its water obligations. As of two weeks before the October 24,2020 deadline, Mexico had paid 89% of its water payment to the US, but owed an additional 240 million cubic meters of water, according to the Comisión Nacional del Agua (Conagua). This was equal to approximately 20% of the water that flows through the Río Conchos and goes into the La Boquilla, El Granero, and Las Vírgenes dams in the state of Chihuahua. Though Mexico ultimately fulfilled its water obligations for the cycle, significant conflict ensued in the weeks leading up to October 24.

Alexandra Helfgott, Wilson Center

The Case of Chihuahua:

Severe droughts over the last few years have left many Chihuahuan farmers concerned about the current lack of water and future water shortages. Many have attempted to secure at least two years’ worth of water to prepare for future droughts, but the government’s transfer of water to the US ahead of the October 24 deadline has depleted their reserves, causing outrage. This led to a politically and diplomatically significant skirmish that began in early September 2020 at Mexico’s northern border at the site of La Boquilla, a dam in the state of Chihuahua, where water from the Río Conchos is stored. The controversy began when farmers blocked authorities from extracting surface water for delivery to the US. The Mexican government soon called in the National Guard to provide backup, but their presence only caused additional violence. Using sticks and rocks, a group of 2,000 protestors, nearly all farmers, succeeded in closing the valves to stop the water flow and push back the National Guard, thus forcing their concession. It was during one of these clashes between the protesting farmers and the National Guard that a protestor, Jessica Silva, was killed by gunfire. After officers detained three people, including Silva and her husband, Jaime Torres, protestors blocked the National Guard’s route with vehicles. The National Guardsmen subsequently opened fire, injuring Torres and killing Silva who has now become a symbol for the fight for water in Chihuahua. In attempts to sidestep conflict and coerce the concerned farmers and occupiers of the La Boquilla dam, the federal government of Mexico has argued that the takeover and closure of the dams in the region have hurt farmers who are further downstream. The government has also promised that farmers will still have access to at least 60% of the water they need, but the farmers, jaded by government promises and wary of increasingly common water shortages, remain unconvinced.

The governor of Texas, Greg Abbott, escalated the controversy by involving the Trump administration, seeking its involvement in the resolution of the dispute. Since the initial conflicts regarding the water transfer, Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), consistently affirmed that Mexico would deliver the water, arguing that reneging on the treaty and trying to negotiate with Trump wasn’t in the best interest of Mexico because it could potentially lead to increased tariffs or even border closures. He went so far as to say that the protests were a “rebellion,” financed by pecan farmers in the region and are strategically organized by politicians for private benefit. AMLO characterized the National Guard’s departure from La Boquilla as “prudent,” as they have strived to avoid violent confrontation with the farmers.

Northern Mexico, one of the most economically successful regions of the country, has traditionally been a conservative stronghold. This is in direct contrast to AMLO whose policies tend to be more liberal and whose supporters are more commonly from the working classes. Chihuahua’s conservative reign has continued under the leadership of PAN governor, Javier Corral, whom AMLO has accused of manipulating the situation into a political ploy by politicizing water for election purposes. The water dispute has turned into a showdown: Morena versus the PAN, the federal government versus the Chihuahua government, and most notably, AMLO versus Corral.

Fulfilling Water Delivery Requirements for the 2015-2020 Cycle:

Despite the recent controversy and violence, Mexico ultimately fulfilled its obligation and ended the 2015-2020 cycle without a shortfall. On October 21, just three days before the official deadline, Mexico and the US signed Minute 325 in which Mexico agreed to transfer the entirety of water in the Amistad and Falcon reservoirs to the US in order to meet its water payment requirements. Though this agreement enabled Mexico to end this cycle without a water debt, the transfer of reservoir water has depleted nearly all of Northern Mexico’s stored water resources. This, along with increasingly common drought conditions, may make it difficult for Mexico to meet municipal water requirements for cities along the border in the future. As such, the Minute stipulates that the US will provide Mexico with humanitarian support by offering the “potential temporary use of U.S. [potable] water” for Mexican communities downstream from the Amistad dam. This offer remains valid until the reservoirs reach 129,714 AF or October 31, 2021 – whichever occurs first and Mexico is responsible for repaying the US in full for the water used. It is important to note that this offer for humanitarian support is subject to Article 3 of the 1944 Treaty which prioritizes water for domestic and municipal purposes, meaning that it cannot be used for agriculture. This is particularly concerning for farmers on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande Valley who, in the near future, will likely face difficulty in securing water for the purposes of irrigation for their crops.

Additionally, Minute 325 also called for the establishment of a Rio Grande Hydrology Work Group to be overseen by the Rio Grande Policy Work Group. Both working groups are tasked with improving management of the river and developing solutions to address water sharing as the Rio Grande basin becomes increasingly drier.

Looking ahead:

The 1944 Treaty has undoubtedly offered a strong and comprehensive framework for binational water management over the last 75 years. However, the treaty does have some shortcomings in terms of issues that it fails to address and as the consequences of climate change become increasingly apparent, it has become clear that demands for water regularly exceed supply. Low prioritization of water for ecological purposes, lack of clarity on the role of reservoirs, and the exclusion of guidelines to manage binational ground water (such as aquifers) are significant concerns in the water management debate that are not addressed by the treaty. The biggest challenges that lie ahead in the water management debate trace their origins back to change – change that is economic, demographic, technological, and climatic. As Mexico and the United States edge further into the future, communities on both sides of the border will be forced to be innovative and strategic, utilizing diplomacy and technology to develop sustainable solutions to address these dynamic changes and ensuing concerns.

About the Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more